Jakob von Gunthen (2018, 70’) is a world premiere of the young Italian director Fabio Condemi who relies on his friend and co-director Fabio Cherstich (and also, as him, a Robert Walser’s avid reader) to put on stage some key and core pages of the homonymous novel of the famous writer who was self-taught and had chosen the isolation in the asylum for the major part of his life.

Fabio Condemi has been among the finalists (and awarded with a special mention) of a competition for Italian directors under 30 promoted by the Venice Theatre Biennale and his director (Antonio Latella) which helps every year to bring on stage an unpublished work and a new name among the young professionals applying. And Jakob von Gunthen has an outstanding bond with literature and the act of reading.

Let’s start from the end: the applauses were infinite at the premiere.

Two students of a pedagogical school for butlers are facing – with intelligent irony – the lack of learning in their institution therefore they cater themselves in order to become a ‘zero’ which is maybe the highest philosophical idea in Walser’s pages: to disappear, to drench in the opposite of the terms ‘ambition’ and ‘power’ which were popular either in Walser’s contemporary society and in ours.

Beside the very faithful transposition of some pages of the novel (the entire audience who did not know this book wanted to read it asap) there is a very cultivated scenic translation which is not only so curated but relies – with a very personal touch and ‘reenacting’ — on the best inventions seen in modern and contemporary art from Beuys (and his unforgettable Capri-Battera) and the Abramovic’s earth-pussy. Timing, lights, the outstanding and ductile costumes were paired with a perfect, and hard, choreography: all the three actors (especially Lavinia Carpentieri but also the great Gabriele Portoghesi and the incredible Xhulio Petushi) were also called to intense physical acts and postures which required a special body training beside to be acting in a ‘classical’ recitative performance.

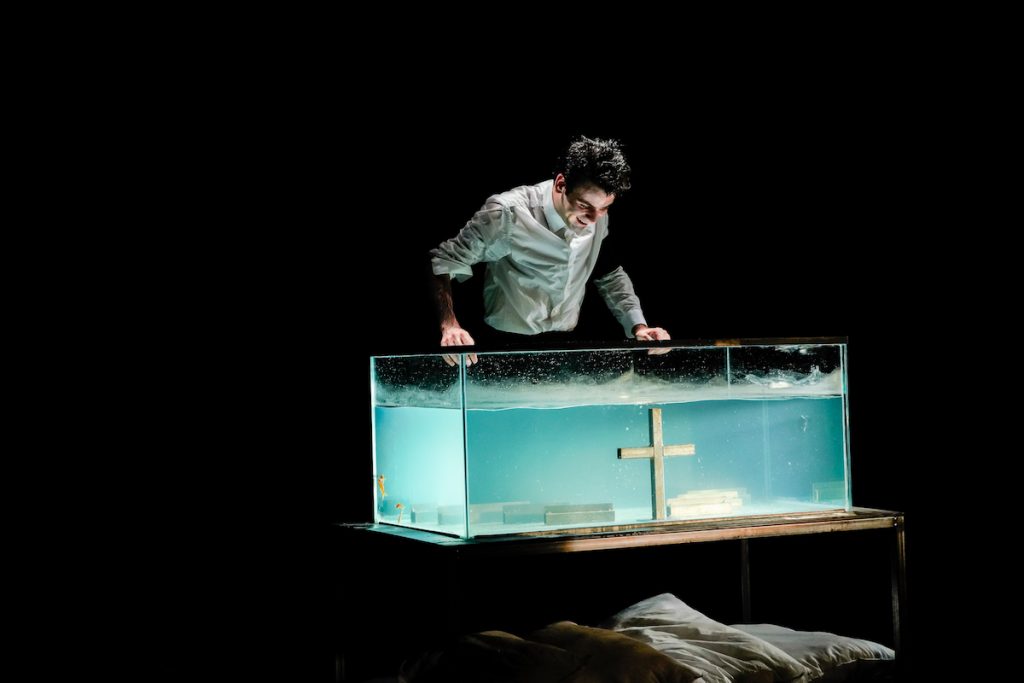

A small note to conclude this comment (a spoiler for this piece will ruin everything!): many directors used the fish-tanks before – as scenic prop, as a storytelling unit, as a carving model to highlight important shifts… In this case, you will see a totally brand new use, recalling, maybe from afar, the Andres Seranno’s Pissing Series/Immersions.

After the premiere, I wanted to know Fabio’s personal and professional path a bit better.

What about your life until now – far from official biographies and with some lines of what there was before theatre and the dreams of your very young age?

I was born in Ferrara (Emilia Romagna) on 1988. I then moved in Marche region with my parents, first in Sassocorvaro and then in Pesaro. As a child, I started reading poetry books (Rimbaud first and Mario Luzi then) and listened to music. I got close to theatre very late and without confidence. After the liceo, I went in Rome to attend the Literature University at La Sapienza but after two years (one spent in Genova at the school of the local teatro stabile, the public theatre), I have been admitted at the Accademia Nazionale d’Arte Drammatica ‘Silvio d’Amico’ in the direction class. I so quitted the university which I’ve already discontentedly attended and devoted myself fully to theatre.

I got as a teacher during the last year the director Giorgio Barberio Corsetti who taught me about the Pier Paolo Pasolini’s theatre. After this encounter – with Corsetti and the Pasolini’s writing – my dissertation essay arose. It was a piece from Bestia da stile by Pier Paolo Pasolini – first in form of a study then in a more definite shape.

After the graduation diploma at the Accademia Silvio d’Amico I started to work with Barberio Corsetti, I am his director aid for opera, theatre and learning projects.

Your super young and super mature theatre seems to me like lava, mixing irony and drama, high level acting and a strenuous work on the body of the actor.

The literature adaptation you choose is very well paired with a stunning visual ‘translation’ as it deals with two souls of the same story.

You declared to get inspired by literature, of which you explore with faith authors and genres by loving the creativity of the firsts and letting their language prevail as they would have wished.

Why did you choose until now the use of literature in theatre in this way?

Is there something pertaining to your overwhelming love for reading?

Or, are you a convinced supporter of the power of books over anything else?

Thank you for the beautiful words. I’m not indeed agreeing with you when you say that my theatre is lava mixing irony and drama (and so on). It would mean that I have a ‘style’ when I treat literary materials I choose to work on and it’s not true. For me, it is true almost the contrary: the text I select to work on (either a theatrical one or pure literature) fully drives the mise en scene. This doesn’t mean to be didactic but to set a dialogue with the text and its form of writing to try to give back its peculiar structure on the scene.

By taking, for example, the Walser’s Jakob Von Gunten it is the proper form of its writing to continuously switching from chatting to monologues to hallucinations until the pages in which the author opens up for us disturbing and boundless landscapes (as the Napoleonic Wars or the desert as last resort to escape) to return, after that and with levity, to chitchats.

This style creates what the author Roberto Calasso defines in his essay Il sonno del calligrafo ‘the Walser’s unstoppable irony’. I measured myself exactly with this type of writing which is, for certain aspects, almost ‘un-representable’. When I worked on Pasolini’s Bestia da stile I was reading a very different text and therefore the work I created was having little in common with this Jakob Von Gunten.

I select some literary texts because they tirelessly ask the director a founding question: what does it mean to ‘represent’ something? When we deal with a text written for the theatre we are often not asking ourselves this question. It is very vital for me – a person who is still strongly feeling that certain lack of confidence with theatre as it was when I was a kid – a sort of dialogue with a matter which escapes for its intrinsic nature to be represented (for instance the Walser’s novel-diary and the prophetic Pasolini’s self-biography Bestia da stile).

What means for you being a theatre professional at 30 in this country and for this country? Do you have any knowledge of what happens to similar age professionals in other countries? What do you like to change and what do you like to preserve?

I think this is a very lively artistic period which deeply confronts itself with the coarseness and the violence both unrestrained in the whole country. There are lots of very authentic artists helping (as the Anagoor, who gained the Silver Lion this year at the Venice Theatre Biennale: their Virgilio brucia is ravishing). The initiative of the director Latella to form a competition giving a production prize in money to young directors under 30 is a very important moment of dialogue for many directors of my age, beyond the competition itself.

I do not know very well the situation in other countries to talk about it.

Next steps?

I’m thinking since a while to Simenon and to his novels without the character of Mr Maigret.

I would love to work on one of these (for instance La Chambre Blueue). But first of all, I would love that my Jakob Von Gunten at which I’m very attached will start to be represented in many theatres. Then I have my works as Giorgio Barberio Corsetti’s assistant where I always enjoy a lot beside to feel them as the occasion for my artistic maturation.

Which is the book with you now and the music you’re listening to? Where the book is placed and where are you in this moment?

I am reading Lettori selvaggi by Giuseppe Montesano (Giunti). I often listen to the latest Edda’s albums. The book is actually used as top for my computer to reply to you, dear Diana!

Where do you see yourself in ten years from now?

I love loneliness a lot and hope to continue to cultivate these passions of mine even in those years, does not matter what I will do in my life.

What did you learn from life until now?

Luckily nothing.

Thank you very much, best

Diana

A dear regard also to you, Diana

Fabio Condemi