Your life until now: an outline shifting around the childhood, the dreams, the family, everything before and after your fine art studies

Before going at the École Boulle (a ‘gravure’ and fine art school) at 16, I had a normal course of studies and I come from a traditional catholic and bourgeois family. They did not have anything in common with gravure: an uncle was a doctor and my mother was a nurse – our father abandoned us and I stayed all alone with my mother.

I was raised with the help of my auntie in Provence who also focused to improve my studies – where I recorded many delays – and to help fixing the problems on my ears. I returned at my mothers’ house around 10-12, during my course of studies I was not eager to have a classic schooling: I wanted to leave it and enroll in an apprenticeship or in an art school. Or in a school to become a veterinary or a farmer.

I see that either creation and ‘care’ are constant treats in your life since then

I think it was an accumulation of experiences. Of recalls. It is sure that if I regard back, I remember only very good moments – as the ones of me and my mother queuing at Grand Palais for an exhibition on Tutankhamen – my uncle, who was very catholic, toured me a lot in churches, in monasteries and in theatre, also at the Chateaux in Loire: even if as children we don’t have the knowledge of the adults, this accumulation of beauty works and we get imbibed in it – willing or not.

And, I see, it becomes a direction for the entire life. Was the fine art school satisfying yourself enough or were you searching beyond it to learn more?

I enrolled in the École Boulle – which is an applied art school – and I learned the etching on glass in an atelier that doesn’t exist anymore in the school, I was the last student of that section in my years.

It is not an apprenticeship school, even if the ateliers like this one were meant to bring something more about the techniques. Beside the 18 hours of ‘ateliers’ per week or something more, we had also a general instruction about the history of the applied arts and professions in this field. We had many others ateliers, like cabinet-making etc.

How many students were enrolled in your years there (you started in 1966)?

There was a quite important, searched and hard exam to be admitted: 600 were applying but only 60 were chosen and admitted. I was very happy to succeed at my first attempt because I had a specific training in evening schools a few days a week for the entire year before the exam. During this training I also built props and without this preparation for sure I wouldn’t be able to pass the hard selection.

After the Boulle, which was my greatest pleasure to attend, I studied at the Paris National Fine Art Academy because my professor at Boulle was also teaching in an atelier there which was dealing the same with glass and stone engraving. My professor was not a professional in engraving and therefore he was showing me only something, but that was not a problem because once enrolled at the Academy I was really able to get a full education in arts and went immediately to research on other things. I had drawing, modeling and carving ateliers as well. We had exceptional teachers as Cesar, Etienne Martin…characters and professionals who were able to forge a different idea of life.

Let’s turn to stones; you work either with hard stones and with fossils. Is the stone looking for you or viceversa?

It something dealing, again, with the notion of progression and with the one of the accumulation of memory. Then it is also a matter of meetings with jewelry makers with whom I started to make little pieces in stone in order to be able to dwell.

Piece by piece, I acquired and solidified my techniques, it took time and I worked almost with any stone, with so many different people…Then I met a very important jewelry maker with whom I worked 25 years. He was the person who triggered my way to work nowadays, he was the person pushing me and the one considering – aussi autriment que forcement – me as an artisan. According to me the artisan, opposite from working in the fine arts even if I use the same tools, confronts directly the matter. Exactly in that relation, and in that confrontation, the work is created. I often speak of fine arts instead of craftsmanship and that’s what I wish to transmit to the younger creators nowadays, working with me.

Returning to your initial question about the stones, I don’t have restrictions in the stones selection and work with both. Opposite from the viewpoint of an artisan, I always look a stone for the emotions it can spark, therefore the work I’m going to create is a bit sublimated by the stone I source.

Do you also select according to colours, resistance and other qualities – maybe because there is a need to follow some trends, like it happens in other craft creations like fashion and design?

I choose really only with my heart.Of course I love an ametiste for its colour but also, some times, for the craziness it embodies, or because the stone comes from an ancient moment of our history, far from us.

A stone can be fabulous because it comes from a very remote part of our planet or from a very different moment of our humanity. Or because it’s the stigma of envy, or of the renaissance; you can read the matter of a stone and see many things in it, even if they’re not all transparent. Then there is also to consider the techniques to work with solidified wood, it’s fabulous. You can imagine that this matter comes from very far, it is very aged.

(by showing me his outstanding collection of fossil stones) This comes from Australia, an excrescence stained in white and green, it is a scar that an insect provoked in a living wood in the very past and has been preserved until us. It’s unique and will be never the same.

It’s very hard to find these fossil stones now, I look for them in the markets and by some importers I know.

Which is your secret to work with such an important array of jewelry makers (like Dior, Cartier, etc) in the same moment where all the brands are usually very ‘jealous’?

Easy: I never sign my work. This is a very borderline subject, by the way, and gatherings as #homofaber (the exhibit where we met and where this conversation took place in French in a very crowded fair booth) must be talking exactly about this by putting the ‘creative hands’ in predominance!

For instance, the applied arts tells always the same story: the artisan, the savoir-faire, the excellence is not translated into ‘design’ (at the least, into the meaning of authorship we give it now to the subject of the ‘maker’).

It’s not for that we’re forgotten, there is the place of the spirit when we work, that’s our history. The majority of the maitres d’arts I know are capable to create their pieces and to sign them in order to make a living.

I never signed my pieces and they’re known everywhere as mine, if I was signing my pieces since the debut of my activity, I did not have had so much work – also nowadays. To date, I am employed – since eight years – at Cartier, where I don’t have the space to sign my pieces as myself.

But you make a difference, a shift nowadays because you’ve teamed a group of young students who will continue the metier-d’art in your atelier…

Yes, I founded my atelier in Paris (I worked with my independent atelier for 35 years before being ‘acquired’ by Cartier) because I asked myself how to transmit my work to younger generations. The problem is that you need a lot of means – and of constance of work flow plus the power to transmit it. There were moments of financial crisis forcing me to close because all the assignments were canceled in one day: in that moment I had the proposal by Cartier to open the atelier inside the company.

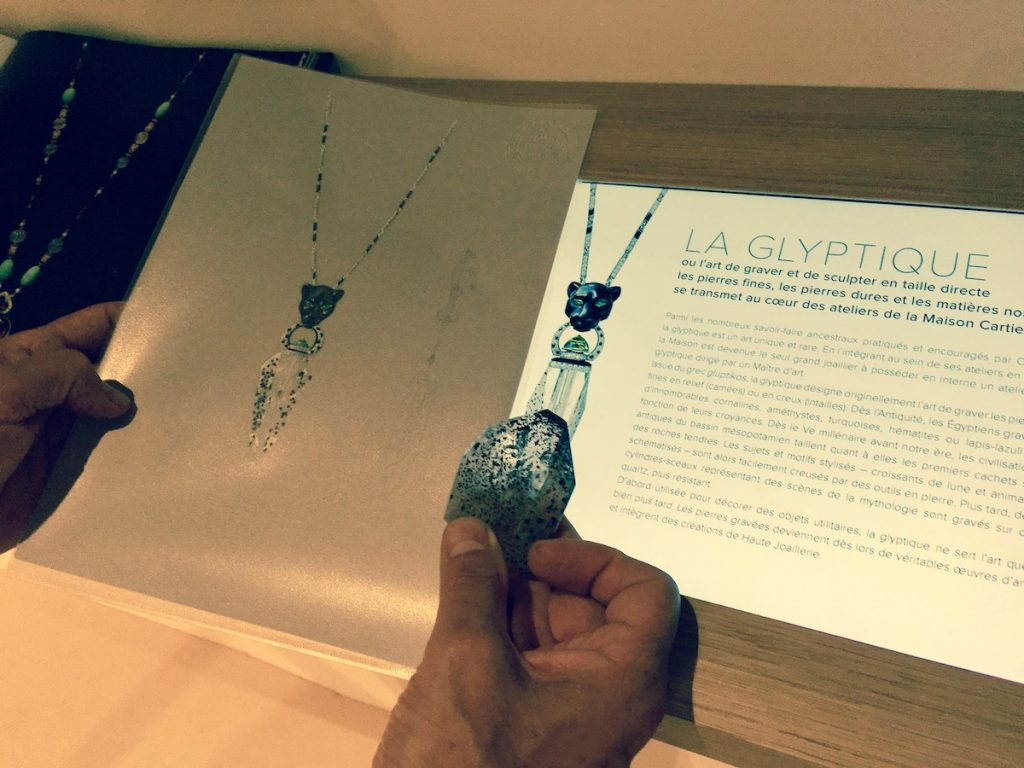

The stone is like the deity of jewelry making, I am a glypticien (engraver) and my work is a cultural immaterial patrimony, it’s a memory of our civilization to be preserved.

What means today being a ‘maitre-d’art’ in France? Are there some legal and practical protections for these professions?

It is a disposition and a process made by Ministry of Culture around 1994 I think, which means to recognize some professionals with exceptional knowledges, aiming to excellence (I don’t tend to excellence so I don’t love very much the definition!) who are willing to transmit their outstanding savoir-faires and ‘designate’ and input some younger practitioners as their ‘students’ that will be able in 13 years to apprehend my knowledge (my designated ‘student’ is Emilie: she worked always with me and it’s more than 13 years). It’s not sufficient this allotted time, 13 years, to learn what you need for this profession. During this time you’re paid normally, which is very important because we don’t deal only to teach and transmit a technique but also a correct way of making a living (and without remuneration this is not possibile).

This latter part you quote has been lost (and globalization had its responsibility in order to destroy this patrimony)….but also subsidies can be polluting the ground…

It’s exactly this the problem, the grants…The maitres-d’art take a grant during the 13 years established by law to transmit their exceptional knowledge but I had already having Emilie working with me and I was already paying her so I did not reach a material aid in my case…And between the state and the private funds, I’d always chosen the private sector, where I found directors who had a very clever position in the business and had the will to invest – as happened with Cartier.

Even if my position is also fragile, I have to thank them to be putting me in this place which is a big machine, a big road roller which goes always further.

My position in this so international company is always the same but the ‘recognition’ is going to enlarge, because the younger staffs acquire the conscience of what this work stands (further the very positive image I vehicle), they know that the engraving job is indispensable and essential in the jewelry making of these years so if we can make it viable, it will be extraordinary. Now it’s fragile like a flower and hard like a stone: it’s very depending by the people I form. Every person I form has also his/her business plans, the prospect on their future, the hurdles of life, of family and of artistic interpretation. There is also a moment in which you have to interpret your style, your means…

It’s a job requiring lots of abnegations, starting always from the piece. It’s very important to make a drawing because some times what is brought in from the designer is not corresponding to my idea of the piece.

Do you have any connection in choosing the stones within their relation with cosmos and planets, astrology and other sciences studying this peculiar relation?

No, I ignore those connections but many people ask me the same question, are you interested in this? Have you seen the picture of my atelier (he shows me a fairy tale…an enchanted place)? It can be possible, you know, that the energy of the stones surrounding me allowed my existence to be so beautiful and so accomplished.

The book and the music with you now?

In relation with my stones, I am always with a book by Roger Caillois [Pierres suivi d’autres textes (Poésie)]. I love to read it from time to time, it’s a collection of poems and a very unique way to write a memoir on stones.

When I am in my atelier I always listen to music. Mostly classic, I love Berio. I love his composition especially for the stone engraving, it’s also perfect to express myself on the Italian stones!

I make my own utensils to engrave the stones.

What did you learn from your life until now?

(he pauses a lot before replying, two very important jewelry makers from Paris are queuing to talk with him and we’re pushed to end our conversation) To have chosen the ‘exposition’ instead of being anonymous as a maitre-d’art if – I have to tell you what I learned from the professional side of my life.

Regarding a more personal side, it’s hard and I have to tell you again that the job I do requires so much abnegation and maybe I saw its discrepancy with the actual life. I wish to quote at this point Pascal: ‘Ne pas savoir rester tranquil dans cette demeure’. We must be able to succeed in what we apply with constance.

The portray of Mr Philippe Nicolas while engraving is courtesy of ‘Association Les Grands Ateliers’, the other pictures are taken by Diana Marrone at #homofaber