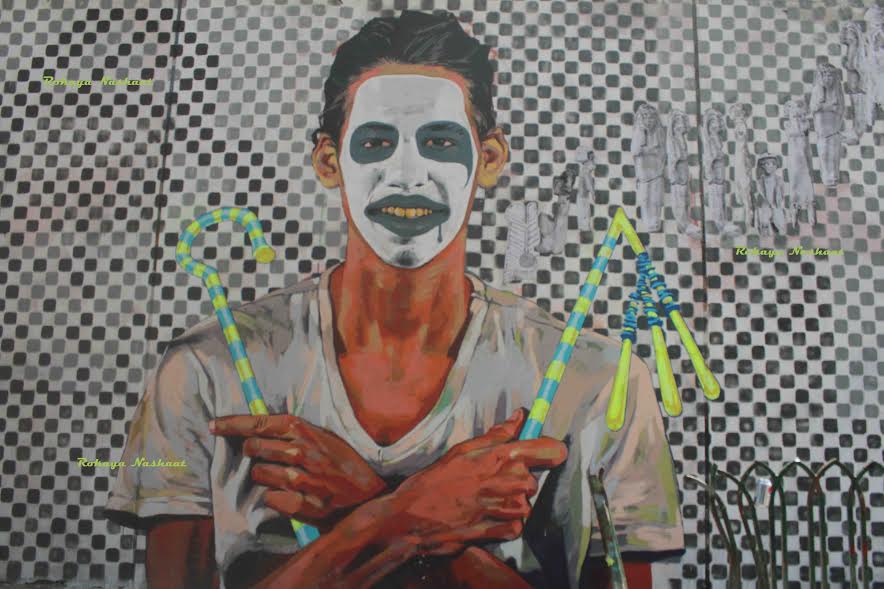

In Luxor we met the Egyptian graffiti artist Ammar Abo Bakr. The thirty year old youngster lives in West el-Balad (neighborhood in the center of Cairo) and is the author of the three most beautiful graffiti on the Mohammed Mahmud street, one of the streets where some of the most heavy fighting took place between the demonstrators and the police, particularly in November 2011, when activists where demonstrating against the military junta, headed by Hussein Tantawi. Amongst these graffiti stands out the young man with fish eyes which represents one of the young men blinded by snipers during the clashes in November 2011 in Tahrir square.

The last graffiti in chronological order on the Mohammed Mahmud street portrays the illustrator Hisham Risk, 19 years old, who went missing and last spring was then found dead in the Sayeda Zeinab morgue. The graffiti have become one of the symbols of the revolts that took place in 2011. Drawings and murals covered the center, bridges and flyovers of Cairo. The artists were able to employ the language of common people to seize the public domain, without yet forgetting the benefit of conquering the words (in classic Arabic: for example, the term “Social Justice”) normally a prerogative of the regime that uses high flung language. In this way thousands of activists confronted the cultural hegemony of the Egyptian authorities. The graffiti however were partly rubbed out during the autumn of 2012, following the election of the ex Islamist president, Mohammed Morsi, and then reappeared after the military coup, becoming real examples of contemporary art. According to the most important Egyptian intellectuals the main artistic effect following the 2011 uprisings are graffiti.

Do you have a recollection of Hisham?

My last graffiti depicts him. He was one of the younger artists of great talent. Not solely on walls did he want the revolution. He got in touch with me a year ago saying he wanted to do graffiti, he wanted to go and study art. And so he started his first year at the Academy. But something went wrong and the radical Islamists of Hazimoun initiated a campaign against Hisham. “Hisham isn’t a Muslim, and speaks badly about Islam”, they would say. For sure between revolution and religion Hisham would have chosen the first. But he was an artist and his friends came from all different political trends. He was a pure revolutionary, against any form of power and religion. The Islamists, from the start of the revolts attempted to mix the cards up and confuse the movement. Our opinion concerning them was certainly not positive, but we can’t deny the ferocity of repression by the army at the time. I also wanted to depict on Hisham’s side some funerary figures from ancient Egypt (I work on Egyptian identity between ancient and modern); I would like to give the people the space to think more. And I’d also like, as in the time of ancient Egypt, that these cult figures of ancient philosophy may accompany him beyond this life.

When did you start doing graffiti?

I studied at the Academy between 1996 and 2001; I started working in the faculty of art in Luxor. It’s really hard surviving here in Egypt. Many artists seem European and have lost their identity. I do research, I believe in the people and not in politics, I don’t like the people from Zamalek (rich neighborhood in the center of Cairo, editor’s note) and from the Opera, the artists have lost everything, they sell paintings to the old capitalists. I would like art to end up everywhere. They teach art and show it in galleries and nobody takes it to the people in the streets. The artists support the regime; they do nothing for the Egyptian people. I started my research in 2004, at the beginning of the revolution I had already drawn up 26 drawing notes, I tried to study people, I would spend time on the street and had not intended presenting myself as a revolutionary. For one year I was giving information about the graffiti depicted on the walls to the people passing by, I never present myself as an artist but as something part of the revolution that uses art.

What do you love about your work?

I’m happy when I finish the work and take a photo and see the reaction of the common people in the street. It’s impressive; I disclose new things. Common people, the families, look upon the wall of the revolution, at the newspaper of the revolution. For me it’s incredible. It’s a pity that artists still show art in the galleries. Of course I’m not against the galleries in Europe, but in Cairo, or Luxor yes. What I paint in the street, after two months, is never the end, but another beginning. So this way I start from the beginning and do something better, I share the walls, this didn’t occur previously.

How do you represent Egyptian society in your works?

Egyptian society gives me the ideas; I get the ideas from Egyptian society. They have accepted what I’ve done on their walls, they respect what I’ve done up until now. When in September the police partially cleaned the walls, during the time of Morsi , the reaction of the people was incredible. They highly criticized the Islamist government. They were all on the streets against this decision. From November 2013 we have made many new graffiti and the police has not erased them, because the reaction of society would have been strong. Without society one cannot do anything.

But yet the revolts are going through a period of complete restraint, following the coup in 2013.

From the last time I painted in Mohammed Mahmud Street, six months have passed, and I’ve done nothing because I was frightened for myself and for my friends; many of them are in prison. The last time I was there to paint the young man with fish eyes I felt at peace. I only went back after six months to paint Hisham. In that moment I felt I had wasted time. I’m like Hanubi, the man that prepares the tomb when someone dies, representing something which is good for the people.

Your culinary passion?

I like ful (mashed lava beans, editor’s note). I love its taste, mixed with tahina (sesame seeds dip, editor’s note) and tomato. I could eat it all the time and not get tired of it. My grandmother used to make a fantastic ful. I like its flavor. I’m not married and always eat street food.

Which is your favorite drink?

I adore Stella (Egyptian beer). I discovered that a Belgium family that lived in Egypt came up with the idea of this beer. This beer is part of our identity.

Do you find any inspiration from Egyptian society?

I read books on Sufism a lot. I like Flamenco, especially the Egyptian one of Ali Khattab. Flamenco is gypsy; part of the gypsies is Egypt, for this reason Egyptians play Flamenco.

Would you like to live somewhere outside of Egypt?

I wouldn’t want to live outside of Egypt. In these last years I’ve travelled a lot to take part in workshops and conferences. If I had to choose I’d like to live in Italy, I’ve been to Sicily and it’s extraordinary. In Berlin I could be with people from all over the world. This is why I could live in Berlin, but when I visited Sicily I fell in love with it immediately. I felt like I was in Egypt and this was extraordinary.

What have you learnt after three years of uprisings?

I’ve learnt that I can’t create anything. Only if I see the people and I learn from common people, on the street, I learn a lot and, if I want to create something, I’m the vehicle between the people and the subject and not much more than this. Or else I couldn’t be creative.

Giuseppe Acconcia

Translation by Paolo Witte