Design objects? Of course we can see them: the whole gamut of designs and devices, from a building to a can opener. The designer gives them a logical, ready-to-use form, premised on certain external parameters: in the case of the can opener, on the structure of a can. The designer of cans, for his part, considers how a can opener functions. That is his external parameter.

So we can perceive the world as a realm of objects and divide these, for example, into houses, streets, traffic lights, kiosks, coffee makers, washing-up bowls, tableware or table linen. Such classification is not without consequences: it leads namely to that concept of design which isolates a certain device—a coffee maker, let’s say—acknowledges its external parameters, and sets itself the goal of making a better, or more attractive one; that is, of producing the type of thing likely to have been described in the 1950s as “Good Form.”

But we can divide the world up in other ways too—and, if I have understood A Pattern Language correctly, that is what Christopher Alexander strives to do. He does not isolate a house, a street or a newsstand in order to perfect its design and construction; instead, he distinguishes an integral composite such as the street corner from other urban composites; for the newsstand thrives on the fact that my bus has not yet arrived, and so I buy a newspaper; and the bus happens to stop here because this is an intersection where passengers can change to other lines. “Street corner” simply tags a phenomenon that encompasses, above and beyond the visible dimension, elements of an organizational system comprised of bus routes, timetables, magazine sales, traffic light sequences and so on.

This way of dividing up our environment also triggers a design impulse—yet one that takes account of the system’s invisible components. What we need, perhaps, so that I won’t miss my bus while scrabbling for change, or because the newsagent is serving another customer, is a simplified method of paying for a newspaper. Some people instantly dream up a new invention—an automatic magazine dispenser with an electric hum—while we imagine intervening somehow in the system: selling magazines for a round sum, or introducing a subscription card that we can simply flash at the newsagent—in any case, some kind of ruling to tackle magazine distribution and that institution “the morning paper.”

What are institutions? Let us forget Christopher Alexander’s street corner in favor of a clearly identifiable institution, the hospital. What is a hospital? Well, a building with long corridors, polished floors, glossy white furniture and little trolleys loaded with tableware for mealtimes.

This view of the hospital takes us back to the traditional design brief: the architect and the designer are called upon to plan hospitals with shorter corridors, more convivial atmospheres and more practical trolleys. As everybody knows however hospitals are now bigger, their corridors longer, the catering service more anonymous and patient care less caring. That is because neither the architect nor the designer were allowed to intervene in the institution per se, but only to improve existing designs and devices within set external parameters.

So, let’s describe the hospital as an institution. Despite all its visible features, it is first and foremost a system of interpersonal relationships. Interpersonal systems are also designed and planned, in part by history and tradition yet also in response to the people alive today. When the Ministry of Health decrees that hospital catering is not the responsibility of medical staff but a management issue—or vice versa—this ruling is part and parcel of the institution’s design.

The hospital owes its existence above all to the three traditional roles of doctor, nurse and patient. The nurse’s role evokes a myriad of associations, from the Virgin Mary through to Ingrid Bergmann, and appears to be clear-cut. In reality it is far from clear-cut, as it incorporates a great number of more or less vital activities. The doctor, historically only a minor figure on the hospital stage, shot to the top in the nineteenth century, on a wave of scientific claims swallowed whole with religious fervor, and perpetuated to this day by TV and trashy novels, with the result that a formidable whiff of heart transplants now permeates even the most backwoods county hospital. And what about the patient? He has no role to play at all, you say? He simply falls ill, through no fault of his own?—Come now, please make up your mind whether you want to be sick or healthy!—Evidently there is an element of choice in the matter. We can—and must—decide one way or the other, otherwise we will irritate our boss—our boss at work, or the hospital boss. A patient lies down—in Chodowiecki’s day he used to sit—or ambles gratefully around the park, convalescing. He resigns himself in any case to the three-role spiel, although it has long been due for an overhaul; but more of that later.

Do other similar institutions exist? Yes, indeed: the night. Yet night is a natural phenomenon, you say? The sun is shining on the Antipodes and so it is dark in our neck of the woods? Anne Cauquelin was the first to posit that the night is artificial. And there is no disputing that human behavior shapes the night one way or another, in line with various man-made institutions. In Switzerland I can work undisturbed after 9 p.m. then go to bed. To give someone a call at that hour is considered impolite. In Germany my telephone is quiet all evening then springs to life at 11 p.m.—for the cheap-rate period begins at 10 p.m., whereupon all international lines are immediately overloaded, and it takes around an hour to get a connection.

Thus the night, which evidently originally had something to do with the dark, is a man-made construct, comprised of opening hours, closing times, price scales, timetables, habits and streetlamps. The night, like the hospital, is in urgent need of redesign. Why does public transport cease to run at precisely the moment people drain their last glass in a wine bar, leaving them no option but to take the wheel? Might not a rethink of opening hours make the streets safer for women obliged to return home on foot, late at night? Are we going to live to see the day also in these climes, when car ownership is the sole guarantee of a measure of safety?

Let’s take another institution, the private household. For the traditional designer, the household is a treasure trove of appliances clamoring to be planned. There are endless things here to invent or improve: coffee makers, food mixers, and dishwashers, to name only a few. The planner deploys novel means to ensure everything stays the same. Moves to reform the household were made around 1900: early mechanization fostered collectivization as well as untold experiments with canteens, public laundries and built-in, centralized vacuum cleaners. Thanks to the invention of small motors these amenities were reinstated later in the private household. Kitchen appliances save housewives’ time, you say? Don’t make me laugh!

The war on dirt is a subsystem within the institution, private household. What is dirt? Why do we fight it? And where does it go after we emerge supposedly victorious? We all know the answer. We just don’t like to admit it. The dirt we fight along with the detergents we use to do so is simply environmental pollution by another name. But dirt is unhygienic, you say, and one cannot avoid a spot of cleaning? Strange! Because people used to clean, even before they knew about hygiene. And besides, the filters used in vacuum cleaners are not fine enough to contain bacteria effectively. Which means that vacuum cleaners merely keep bacteria in circulation. What a shame for the vacuum cleaner, the designers’ favorite brainchild!

(….)

Design Is Invisible, Lucius Burckhardt (1925–2003), 1980

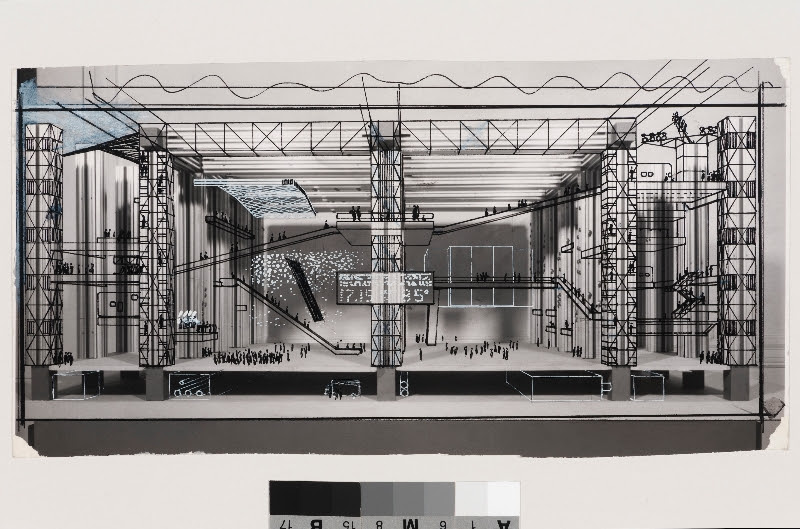

Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price have exhibited in a performative setting (Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price – A stroll through a fun palace) at the Swiss Pavilion in Giardini, Venice (Architecture Biennale, 2014).

Credits for the cover image:

Cedric Price, Fun Palace: Interior perspective, 1964, black and white ink over gelatin silver print. 12.6 x 24.8 cm. DR1995:0188:518. Cedric Price fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal.