Venice Movie Festival is often opening eyes onto unexpected movies. Zumiriki has been, so far, the most unexpected.

Written, filmed, edited and above all interpreted by one person, Oskar Alegria, it is digging in his personal memories and adapting himself to live as an hermit for the entire duration of the ‘experiment’. The title is borrowed from a Basque word meaning “island in the middle of the river”.

He moved on a river bank, close by to where in the past the family house was located before the land has been inundated.

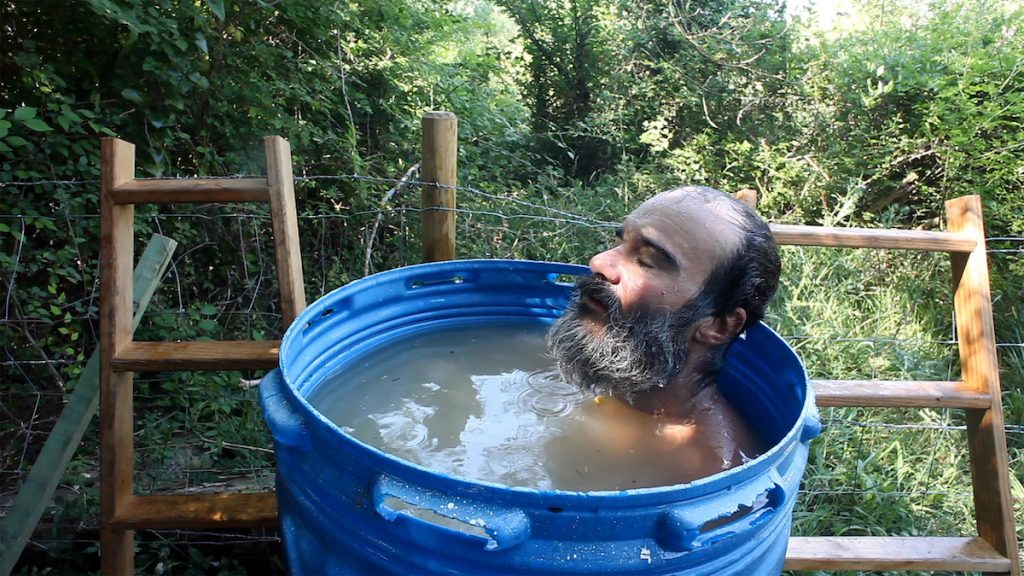

He built a shack in the wood, ‘a Robinson Crusoe of memory. The adventure lasted four months in the spring and summer of 2018, and was lmed on the Arga River as it passes through Gorriza-Iriberri in Navarre in the north of Spain; this is a river gorge that has created a small, miraculously-intact paradise.

On the most inaccessible side of the river, the lmmaker installed his cabin and was accompanied in his isolation by a small vegetable patch, two chickens and a clock that had stopped forever at 11.36 and 23 seconds. There are no other human beings, no artificial light, no dogs barking, only a road 212 metres away, which you can see on the other side of the river; half-understood news arrives in the form of murmurs from passing cyclists, and sometimes shots can be heard. He took four remote cameras for recording nature with him, to lm what the night hides from the day. 70 books, a hammock. Canned and preserved food. Bottled spring water. Batteries, and a couple of solar panels to recharge them. Four months without money, without speaking, without an ID card, without light, without keys. But with the most important item, a chair; the main thing needed for doing what a castaway does: wait. This movie is a lm about waiting, waiting for nothing.’

Can you imagine how much poetry Zumiriki hosts and gifts to you?

What follows is a conversation taking place between Oskar and me on long distance in the aftermath of the presentation of the movie: we will hope you can see it soon in your cities!

Your life in a few words, especially the parts not depicted in the self-biographical picture.

Since I was a child I love to hide myself and be alone. I have notice that my freedom feeds on two main ingredients: loneliness and secret. This project is perhaps the one I have experienced most all this.

But there is a phrase by Jean Baudrillard that I have always had in mind: in the game of hiding, one should never hide very well, because the others will stop looking for him.

Basque language is more than a narrative element, it’s a pillar to depict a way of living and thinking especially in the chapter of the movie where you tell about the last shepherds living in total isolation. Can you tell us more about Basque identity placement nowadays especially in relation to the actual situation of your country after the turmoil with Catalogna?

I think these projects are of a low intensity ideology. I don’t want to make pamphlets or manifests. I believe much more in poetics. And in the gesture. But yes, Basque language is for me a landscape. Not a way of thinking. I believe, as our great linguist Koldo Mitxelena maintained, that language does not give a thought. But it does tie you to a specific landscape and a way of being on earth. It is what the scarecrows represent that is a very present element in my work. As in the collection of photos I make with scarecrows from around the world. A scarecrow shows the exact portrait of his author especially in his way of being, in his presence, in his relationship as a human figure on the landscape. In Japan the scarecrows are crestfallen, on the Greek islands they look up at the horizon. There must be a reason. If a scarecrow is not well done, the animals attack the fruit, they know that it is not the real portrait of its owner, as good art critics.

I’d never had the chance to see a movie like yours before – doesn’t matter how much I’m a movie addict. It’s beyond any canonical form of plot and script, set design and DOP inventions – all made by one person: you.

Among all the qualities of the movie, I’m stunned by the place literature and the poetry of gesture including drawing with objects have. Can you tell me your relation with sculpture, literature and writing beyond the language ‘cult’ itself?

It is a shipwrecked movie in the sense of handmade craft, as an artisanal object. When you are in an isolated and remote paradise you have to make the movie with the objects you find at hand: branches, stones, wood… I think that chalk is a very important element in the film, I have thought about it when I left the adventure, our memories are made of chalk, they set a time but ephemeral, and this is a movie that is drawn on the walls. Also the performative fact of self-filming, I think it has a part focused on nature. I like to see the idea of the bird that builds its nest and sculpts it with its own body. It is a bricklayer without arms, only with the pressure of his chest, with the molding of his beats, he manages to get used to a house that is the image and reflection of his own body. I think this movie is also made very physical, molded with the body itself… to reach a dream: to make a film in which to stay and live.

You’d shown incredible talents to make this movie, can you tell us a talent you miss?

In relation to the previous question, I am very clumsy with my hands, I do not control the DIY and it is something I envy, or the garden, I do not get that skill green. But in this film I wanted to take off my mental work and discover a new person, take the drill for the first time, get stained, sweat, be able to make a seven-ingredient salad without going to the supermarket. I like that Greek concept of mixing physical achievement with mental feat. Cynics created their philosophical current in a gym. In the attempt to return to a submerged island and climb the trees of my childhood in the middle of the river … I have had to mix the sporting deed but above it I have always tried to keep the poetic gesture in the foreground.

The relation with your city: what do you feel to get from it and what do you feel to give it back?

My city Pamplona is just the size specified by the Basque writing Unamuno: in 15 minutes walking you arrive from the asphalt to a path. It is increasingly difficult but it is true that it is a city that allows you to get away to the forest in a few kilometers. And that is important to me. My paradise, for example, is only half an hour away by car and it is still easier to reach it by water than by land, as if it were a definition of a remote place in the Amazon.

Where do you see yourself in ten years from now?

I think I will continue not far from where I am now, finishing a third movie that will be the last of a trilogy. This one I just did I think is the third one. I made only one, a first one five years ago, but I think the one that is left to be done will be the second one, it combines both. The first, The Search for Emak Bakia, tells the story of the search for a mysterious house, the latter speaks of a large tree in the middle of a river … following the idea of the first images of Gaston Bachelard, the one I have to do next and last is one film about a path.

What did you learn from life so far?

I have found more than learned that small can be very large, that the owl always chooses the same branch to sing in the forest, a golden branch, from which its ancestors also sang. It is the branch from which the echo of its mountains takes its song further.

#mostradelcinema

Zumiriki next screening will be on October 8 at Cinema Zenith, Perugia (Italy) at Perso Film Festival on Tuesday October 8, 9.30pm at Cinema Zenith