Learning about a country (Japan) through the working spaces of its artists and designers is an uncanny perspective – rich in senses and meanings.

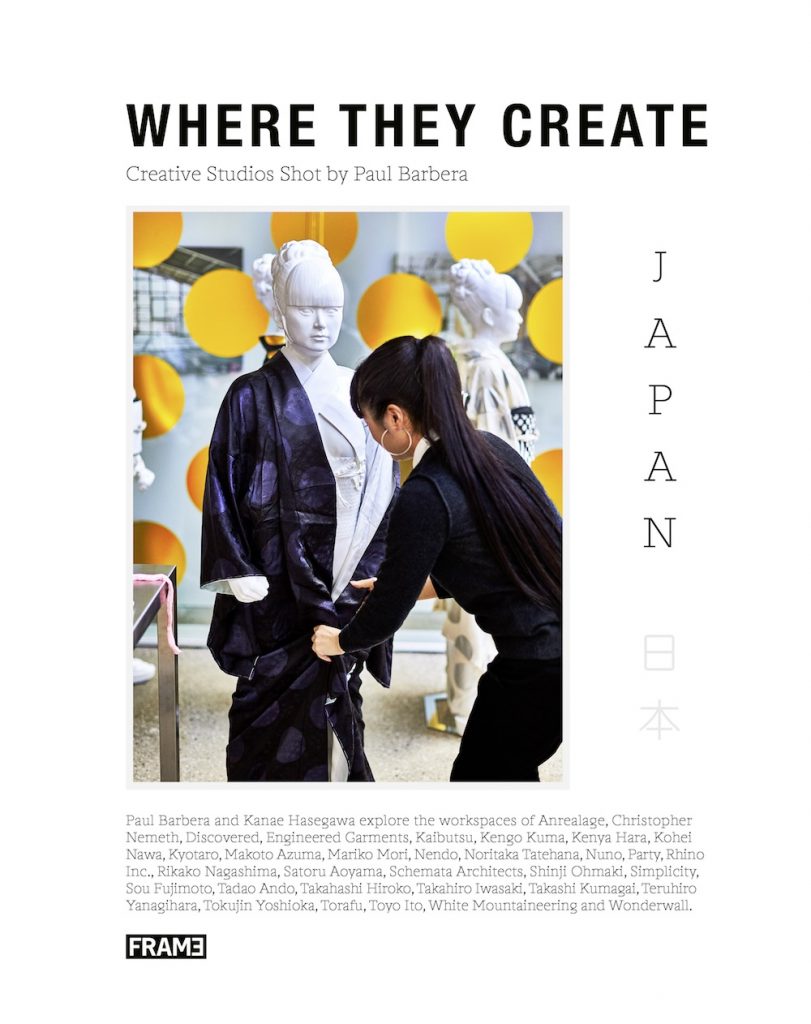

Two are the authors who gift it to us: an Australian photographer, born in Melbourne by Italian ancestors now living in NY City (Paul Barbera). And a Japanese curator, writer and journalist: Kanae Hasegawa. How do they succeed in it? By doing what they do better. Barbera was working on this topic, his long-term self-commissioned project, first on his blog (wheretheycreate.com) and then on luxury and lifestyle magazines. It is a portraiture of artists’ spaces and of themselves by using a technique we can borrow by written storytelling as the ‘here and now’ – i.e. natural light, zero make up, zero styling and a casual day of their work time, not forgetting to include spaces of creatives from any sector: from fashion to design and architecture and beyond. It is made in such distinctive way that any of the viewers can pick, in its vividness, a microcosm of a ‘person from this world’ in the act of working in any usual day of his life.

Where They Create Japan arises from the intuition of its authors and from a specific sensibility of its publisher, a Dutch company called Frame that also put on the market two magazines (art, design) and many titles spanning from technical manuals to food for souls ones (perfect for the same creatives portrayed by Barbera). Well curated and very solidly designed, once you grab it in your hands you should know to manage a very borderline publication.

It is more an alphabet for the mind than a treaty on makers – Where They Create Japan selects professionals with very diverging ages and preferred medias. It traces a map of Japan within the chosen places to set a studio, by showing a sensibility toward one district and/or another and by detecting the emersion of new productive and residential areas; it is also able to define the great place craftsmanship still has in the country – unaltered in centuries. And how it exports this philosophy in the rest of the world, by often embedding these creatives in multinational brands, given their migrators’ habits.

If you’re about to settle in Japan, if you do not read magazine and all at a sudden you wish to get well informed on the creative scene of this country, if you’re curious to understand how the designers’ work is in a island far away from your usual work scene, Where They Create Japan could be also a book able to fulfill these needs.

Kanae Hasegawa – who defines the Barbera’s touch ‘serene, restrained, beautiful’ – is right: the photographer indulges in some (building, furnishing, creational) details of these spaces that make all together the portrait of the interviewed person even more meaningful and talkative and powerful, speaking also of the inner facets of the subject. The real ‘narration’ of the stories is made with the more strictly textual component of the book, author Hasegawa: short introductions and long and accurate interviews to each of the portrayed. Readers will not only discover a creative milieu but the sensitivity of a country, its ethic, its schools, and its ‘emotional’ architecture beside the material and the figurative ones.

Who are the subjects enhanced by Barbera’s focus and Hasegawa’s pen? There are architects, artists, artistic directors, graphic and furniture and textile and floral designers…There are very famous names, as architects Kengo Kuma and Tadao Ando. Or as the artist Mariko Mori who tells about her white tea room (she also makes the tea for Barbera and tells also what she does when she resides in Japan within respect with what she indeed does in the other two of her cities: London where she searches inspirations and New York where she realizes them).

Beside them, other creatives open up themselves and their spaces: Anrealage (behind the cult brand whose name is a combination of three words – Real, Unreal, Age – there is a fashion designer born on 1980 as few others reviewed in the book: Kunihiko Morinaga), Christopher Nemeth, Discovered, Engineered Garments, Kaibutsu (a web designer, Yosuke Kitani), Kenya Hara, Kohei Nawa, Kyotaro, Makoto/Azuma, Nendo (i.e. the furniture designer Oki Sato), Noritaka Tatehana, Nuno (the textile designer Reiko Sudo), Party, Rhino Inc., Rikako Nagashima, Satoru Aoyama, Schemata Architects, Shinji Ohmaki, Simplicity, Sou Fujimoto, Takahashi Hiroko, Takahiro Iwasaki, Takashi Kumagai, Teruhiro Yanagihara, Tokujin Yoshioka, Torafu, Toyo Ito, White Mountaineering, Wonderwall (interior design).

Among them, some appreciate other professionals in the book and among the junior, some also met in person – as happened to Kitani who met Mr Azuma/Makoto at a Hermès event (and took inspiration by his floral design to decorate his heavily concrete shaped office with green). Age ranges vary quite a lot: it is a sort of X ray of creatives and their working worlds (the Japan one is quite different from what Europeans or Americans experience) spanning from who is 70 years old and who is much less of its half.

This book tells what you can see but above all what you can’t: from the creative to the living habits (how many hours at work, which preferred mean to commute – there is who goes to work everyday with the cat from home – which is the favourite window for a pause and for a glance and why, if to work with music or with silence), until to unveil spaces that are normally precluded (it is certainly to be said that any of these spaces are precluded to those are not invited to access them: none of them is a shop or a gallery). One of these is peculiar, maybe the most interesting story because it better tells about the liason between work methods and Shintoism. We speak of Makoto, a brand of an ante-litteram florist (and botanist) placed in an empty shop: he keeps his creations in the basement (and they’re saved from impermanence thanks to Shunsuke Shiinoki’s pictures). Why he makes like that you will discover in the book….

Four are those prefacing the whole bunch of stories but also tell about their relation with Japan and their meaning of the book (beside Barbera himself): there is who is born there (like Nicola Formichetti, actually the artistic director of Diesel; like the former Serie A soccer player Hidetoshi Nakata); there is who constantly travels there for work and because of the love for the country (Tyler Brulè, Wallpaper* creator, and now, since a while, the Monocle one). Last but not least, the most long-lived of the volume: Mineaki Saito (Hermès).

Publication details

• Release: 1 November 2016

• Photography by Paul Barbera

• Written by Kanae Hasegawa

• English

• Graphic design by Frame Publishers

• 200 x 255 mm / 312 pages / full colour / soft cover

• ISBN 978-94-92311-02-3

• €29.00 (order)

We’ve interviewed Paul Barbera, read his full story here